12. role models

Oct. 21st, 2005 05:38 am| ecce respondeo dicenti, ‘quid faciebat deus antequam faceret caelum et terram?’ respondeo non illud quod quidam respondisse perhibetur, ioculariter eludens quaestionis violentiam: ‘alta,’ inquit, ‘scrutantibus gehennas parabat.’ aliud est videre, aliud ridere: haec non respondeo. — Aurelius Augustinus, Confessiones See, I answer him that asketh, “What did God before He made heaven and earth?” I answer not as one is said to have done merrily (eluding the pressure of the question), “He was preparing hell (saith he) for pryers into mysteries.” It is one thing to answer enquiries, another to make sport of enquirers. So I answer not.— Augustine of Hippo, Confessions |

|

| La Fontaine, entendant plaindre le sort des damnés au milieu du feu de l’Enfer, dit : « Je me flatte qu’ils s’y accoutument, et qu’à la fin, ils sont là comme le poisson dans l’eau. » — Chamfort, Maximes et Pensées, Caractères et Anecdotes La Fontaine, hearing complaints of the lot of the damned in the midst of hellfire, said: “I trust that they get accustomed to it, and that in the end, they rest there as fish in water.”— Chamfort, Maxims and Thoughts, Characters and Anecdotes |

|

| FEU. Purifie tout. — Quand on entend crier « au feu », on doit commencer par perdre la tête. — Gustave Flaubert, Le Dictionnaire des idées reçues FIRE. Purifies everything. — Upon hearing the cry of “Fire!”, one must begin by losing his head.— Gustave Flaubert, Dictionary of Received Ideas |

|

| Il y a du Dante, en effet, dans l’auteur des Fleurs du Mal, mais c’est du Dante d’une époque déchue, c’est du Dante athée et moderne, du Dante venu après Voltaire, dans un temps qui n’aura point de saint Thomas. — Jules Barbey D’Aurevilly, Les Poètes There is Dante, in effect, in the author of the Flowers of Evil, but it is a Dante of the fallen era, an atheistic and modern Dante, a Dante who comes after Voltaire, in a time that will have no saint Thomas.— Jules Barbey D’Aurevilly, The Poets[0] |

| Δεῦτε πρός με πάντες οἱ κοπιῶντες καὶ πεφορτισμένοι, κἀγὼ ἀναπαύσω ὑμᾶς. | Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. |

William Blake, Christ Blessing the Little Children

Pelagius urged men to to follow Jesus in attaining Godly perfection.[2] His call finds its counterparts in the outer reaches of ambition, regardless of its object. Thus an ambitious alien entrepreneur can be heard intoning: “I never do anything I do not like. I do not moralize. I never distinguish between work and pleasure. I admire Bill Gates. I aspire for a private meeting with Bill Gates. I want to ask, ‘What drives you?’” An alien of a different stripe, a self-made exile who fancies himself above cupidity, one who has renounced prayer and denounced the rotten face of its addressee, is likely to aspire to another kind of encounter. Has he a better role model than Milton’s Satan?

Witness this fallen angel, whom Charles Baudelaire identifies as the model of virile beauty:[3]

| J’ai trouvé la définition du Beau, — de mon Beau. C’est quelque chose d’ardent et de triste, quelque chose d’un peu vague, laissant carrière à la conjecture. Je vais, si l’on veut, appliquer mes idées à un objet sensible, à l’objet par exemple, le plus intéressant dans la société, à un visage de femme. Une tête séduisante et belle, une tête de femme, veux-je dire, c’est une tête qui fait rêver à la fois, — mais d’une manière confuse, — de volupté et de tristesse ; qui comporte une idée de mélancolie, de lassitude, même de satiété, — soit une idée contraire, c’est-à-dire une ardeur, un désir de vivre, associés avec une Une belle tête d’homme n’a pas besoin de comporter, aux yeux d’un homme bien entendu, — excepté, peut-être, aux yeux d’une femme, — cette idée de volupté, qui, dans un visage de femme |

I have found the definition of Beauty, — of my Beauty. It is something fiery and sad, something a little vague, allowing for freedom of conjecture. I will, if I may, apply my ideas to a concrete object, for example to the most interesting of objects in the society, to a woman’s face. A seductive and beautiful head, a woman’s head, that is, is one that inspires all at once, —but in a confused fashion,—dreams of both voluptuousness and sadness; one that carries with it the idea of melancholy, of lassitude, even of satiety, — be it a contrary idea, in other words an ardor, a desire to live, connected to a A handsome man’s head need not convey, naturally, to the eyes of a man, — except, perhaps, to the eyes of a woman, — this idea of voluptuousness, which, in a woman’s face |

William Blake, Satan Inflicting Boils on Job

Thus far these beyondWhat of the moral inspiration drawn from this refulgent antagonist? If our man must differ from his satanic role model, it is in refusing the contrarian logic that compels th’ Arch-Fiend to upend the commandments of his adversary:[5]

Compare of mortal prowess, yet observ’d

Their dread commander: he above the rest

In shape and gesture proudly eminent

Stood like a Tow’r; his form had yet not lost

All her original brightness, nor appear’d

Less than Arch-Angel ruin’d, and th’ excess

Of Glory obscur’d: As when the Sun new ris’n

Looks through the Horizontal misty Air

Shorn of his Beams, or from behind the Moon

In dim Eclipse disastrous twilight sheds

On half the Nations, and with fear of change

Perplexes Monarchs. Dark’n’d so, yet shone

Above them all th’ Arch-Angel: but his face

Deep scars of Thunder had intrencht, and care

Sat on his faded cheek, but under Brows

Of dauntless courage, and considerate Pride

Waiting revenge: cruel his eye, but cast

Signs of remorse and passion to behold

The fellows of his crime, the followers rather

(Far other once beheld in bliss), condemn’d

Forever now to have their lot in pain,

Millions of Spirits for his fault amerc’t

Of Heav’n, and from Eternal Splendors flung

For his revolt, yet faithful now they stood,

Their Glory wither’d.

Fall’n Cherub, to be weak is miserableTo react in this fashion would grant too much credit to his absconded adversary.[6] No fault of the artist’s betters can serve as his excuse for forswearing his own quest for realizing values in harmony with his place in the cosmos. In drawing upon the wellspring of contempt that enables him to prevail over adversity, he would sooner efface his own personal singularity than invest the entirety of his environment with a face that mirrors his fairest gladness, let alone his scariest grimace. True independence from His inmost counsels consists in disdain, not defiance.

Doing or Suffering: but of this be sure

To do aught good never will be our task,

But ever to do ill our sole delight,

As being the contrary to his high will

Whom we resist. If then his Providence

Out of our evil seek to bring forth good,

Our labor must be to pervert that end,

And out of good still to find means of evil;

Which oft-times may succeed, so as perhaps

Shall grieve him, if I fail not, and disturb

His inmost counsels from their destin’d aim.

But what of the eternity of damnation threatened as the sinner’s recompense for finding an infinity of joy in a single second? An adequate understanding of this destiny depends on accounting for its classic portrayal. It is aptly said of Jean-Jacques that he was ridden by guilt but incapable of contrition.[7] How well this account defines the sinners’ predicament in Dante’s Inferno! To these unfortunates, contrition is no longer available in the finality of their divine punishment that robs them of the good of the intellect.[8] In anticipation of this privation, the sinner is left with two strategies for responding to his guilt. The perpetual rebellion of Milton’s Satan serves as the only available response to Dante.

While Plato attributes the discovery of Hell to Socrates, its definitive and final nature is a novelty of Christian origins.[9] Eschatology is the doctrine of the last things, and one feature of this idea of culmination or consummation is that there is a finality to it. The basis of infernal penology that Dante derives from Aquinas is evident in the words of Jesus referring to the fire of Gehenna, γέεννα,[10] and calling upon his followers to fear him who is able to destroy both soul and body therein.[11] Jesus then prophesies that sinners shall be cast out into outer darkness, tenebrae exteriores, σκότος τὸ ἐξώτερος, and the furnace of fire, caminus ignis, κάμινος τό πυρός; there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth.[12] Most pointedly, he speaks of eternal fire, ignis aeternus, τὸ πῦρ τὸ αἰώνιον, and eternal punishment, supplicium aeternus, κόλασις αἰώνιον.[13] While classical antiquity singled out exemplary nonconformists such as Sisyphus and Tityus,[14] forever to have their lot in pain, Jesus became the first prophet to condemn likewise all rebels against God’s will.

The most exquisite punishment is reserved for the greatest of sinners. Thomas Aquinas identifies the sins of fallen angels as pride or superbia and envy or invidia.[15] Even so, he places Satan not among the highest angelic choir of the Seraphim, but at the next rung, the Cherubim. For the Cherubim are interpreted as fulness of knowledge or plenitudo scientiae, but the Seraphim are interpreted as the heat of charity or ardentes sive incedentes. For unlike the heat of charity, fulness of knowledge is compatible with mortal sin.[16] Thus Aquinas follows the Aristotelian account of virtue, declaring against the Socratic identity of virtue with knowledge.[17] From this position, he is able to consign Satan to Hell despite his intellectual perfection. This perfection is realized in radically disparate fashions by Dante Alighieri and John Milton.

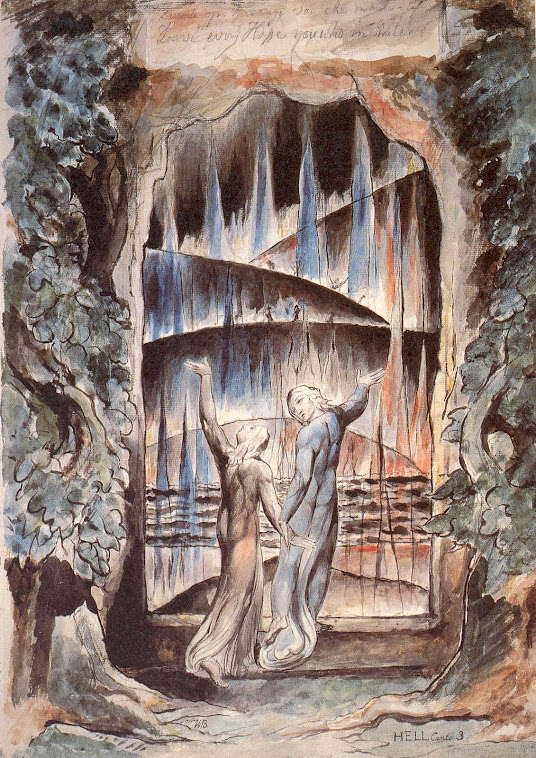

Dante Alighieri spells out the moral nature of Hell at the beginning of the Third Canto of his Inferno:[18]

| «Giustizia mosse il mio alto fattore: fecemi la divina podestate, la somma sapienza e ‘l primo amore. |

JUSTICE URGED ON MY HIGH ARTIFICER; MY MAKER WAS DIVINE AUTHORITY, THE HIGHEST WISDOM, AND THE PRIMAL LOVE. |

| Dinanzi a me non fuor cose create se non etterne, e io etterno duro. Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’intrate». |

BEFORE ME NOTHING BUT ETERNAL THINGS WERE MADE, AND I ENDURE ETERNALLY. ABANDON EVERY HOPE, WHO ENTER HERE. |

| Queste parole di colore oscuro vid’io scritte al sommo d’una porta; per ch’io: «Maestro, il senso lor m’è duro». |

These words ― their aspect was obscure ― I read inscribed above a gateway, and I said: “Master, their meaning is difficult for me.” |

| Ed elli a me, come persona accorta: «Qui si convien lasciare ogne sospetto; ogne viltà convien che qui sia morta. |

And he to me, as one who comprehends: “Here one must leave behind all hesitation; here every cowardice must meet its death. |

| Noi siam venuti al loco ov’i’ t’ho detto che tu vedrai le genti dolorose c’hanno perduto il ben de l’intelletto». |

For we have reached the place of which I spoke, where you will see the miserable people, those who have lost the good of the intellect.” |

William Blake, Gate of Hell

| Così della induzione della perfezione seconda le scienze sono cagione in noi; per l’abito delle quali potemo la veritade speculare, che è ultima perfezione nostra, sì come dice lo Filosofo nel sesto dell’Etica, quando dice che ‘l vero è lo bene dello ‘ntelletto. | Similarly, the sciences are the cause in us of bringing about the second perfection, by the possession of which we are able to contemplate the truth, which is our ultimate perfection, as the Philosopher says in the sixth book of the Ethics when he says that truth is the good of the intellect. |

| ἔστι δ’ ὅπερ ἐν διανοίᾳ κατάφασις καὶ ἀπόφασις, τοῦτ’ ἐν ὀρέξει δίωξις καὶ φυγή: ὥστ’ ἐπειδὴ ἡ ἠθικὴ ἀρετὴ ἕξις προαιρετική, ἡ δὲ προαίρεσις ὄρεξις βουλευτική, δεῖ διὰ ταῦτα μὲν τόν τε λόγον ἀληθῆ εἶναι καὶ τὴν ὄρεξιν ὀρθήν, εἴπερ ἡ προαίρεσις σπουδαία, καὶ τὰ αὐτὰ τὸν μὲν φάναι τὴν δὲ διώκειν. αὕτη μὲν οὖν ἡ διάνοια καὶ ἡ ἀλήθεια πρακτική: τῆς δὲ θεωρητικῆς διανοίας καὶ μὴ πρακτικῆς μηδὲ ποιητικῆς τὸ εὖ καὶ κακῶς τἀληθές ἐστι καὶ ψεῦδος ̔τοῦτο γάρ ἐστι παντὸς διανοητικοῦ ἔργον̓: τοῦ δὲ πρακτικοῦ καὶ διανοητικοῦ ἀλήθεια ὁμολόγως ἔχουσα τῇ ὀρέξει τῇ ὀρθῇ. | Pursuit and avoidance in the sphere of Desire correspond to affirmation and denial in the sphere of the Intellect. Hence inasmuch as moral virtue is a disposition of the mind in regard to choice, and choice is deliberate desire, it follows that, if the choice is to be good, both the principle must be true and the desire right, and that desire must pursue the same things as principle affirms. We are here speaking of practical thinking, and of the attainment of truth in regard to action; with speculative thought, which is not concerned with action or production, right and wrong functioning consist in the attainment of truth and falsehood respectively. The attainment of truth is indeed the function of every part of the intellect, but that of the practical intelligence is the attainment of truth corresponding to right desire. |

| Lo ‘mperador del doloroso regno da mezzo ‘l petto uscìa fuor de la ghiaccia; e più con un gigante io mi convegno, |

The emperor of the despondent kingdom so towered from the ice, up from midchest, that I match better with a giant’s breadth |

| che i giganti non fan con le sue braccia: vedi oggimai quant’esser dee quel tutto ch’a così fatta parte si confaccia. |

than giants match the measure of his arms; now you can gauge the size of all of him if it is in proportion to such parts. |

| S’el fu sì bel com’elli è ora brutto, e contra ‘l suo fattore alzò le ciglia, ben dee da lui proceder ogne lutto. |

If he was once as handsome as he now is ugly and, despite that, raised his brows against his Maker, one can understand |

| Oh quanto parve a me gran maraviglia quand’io vidi tre facce a la sua testa! L’una dinanzi, e quella era vermiglia; |

how every sorrow has its source in him! I marveled when I saw that, on his head, he had three faces: one — in front — bloodred; |

| l’altr’eran due, che s’aggiugnieno a questa sovresso ‘l mezzo di ciascuna spalla, e sé giugnieno al loco de la cresta: |

and then another two that, just above the midpoint of each shoulder, joined the first; and at the crown, all three were reattached; |

| e la destra parea tra bianca e gialla; la sinistra a vedere era tal, quali vegnon di là onde ‘l Nilo s’avvalla. |

the right looked somewhat yellow, somewhat white; the left in its appearance was like those who come from where the Nile, descending, flows. |

| Sotto ciascuna uscivan due grand’ali, quanto si convenia a tanto uccello: vele di mar non vid’io mai cotali. |

Beneath each face of his, two wings spread out, as broad as suited so immense a bird: I’ve never seen a ship with sails so wide. |

| Non avean penne, ma di vispistrello era lor modo; e quelle svolazzava, sì che tre venti si movean da ello: |

They had no feathers, but were fashioned like a bat’s; and he was agitating them, so that three winds made their way out from him — |

| quindi Cocito tutto s’aggelava. Con sei occhi piangea, e per tre menti gocciava ‘l pianto e sanguinosa bava. |

and all Cocytus froze before those winds. He wept out of six eyes; and down three chins, tears gushed together with a bloody froth. |

| Da ogne bocca dirompea co’ denti un peccatore, a guisa di maciulla, sì che tre ne facea così dolenti. |

Within each mouth — he used it like a grinder — with gnashing teeth he tore to bits a sinner, so that he brought much pain to three at once. |

| A quel dinanzi il mordere era nulla verso ‘l graffiar, che talvolta la schiena rimanea de la pelle tutta brulla. |

The forward sinner found that biting nothing when matched against the clawing, for at times his back was stripped completely of its hide. |

| «Quell’anima là sù c’ha maggior pena», disse ‘l maestro, «è Giuda Scariotto, che ‘l capo ha dentro e fuor le gambe mena. |

“That soul up there who has to suffer most,” my master said: “Judas Iscariot — his head inside, he jerks his legs without. |

| De li altri due c’hanno il capo di sotto, quel che pende dal nero ceffo è Bruto: vedi come si storce, e non fa motto!; |

Of those two others, with their heads beneath, the one who hangs from that black snout is Brutus — see how he writhes and does not say a word! |

| e l’altro è Cassio che par sì membruto. Ma la notte risurge, e oramai è da partir, ché tutto avem veduto». |

That other, who seems so robust, is Cassius. But night is come again, and it is time for us to leave; we have seen everything.” |

William Blake, Lucifer

In Proposition XXXVII of Part IV of the Ethics, Benedict Spinoza asserts that the good that every man who follows after virtue wants for himself, he also desires for other men; and this Desire is greater as his knowledge of God is greater. (Bonum quod unusquisque qui sectatur virtutem, sibi appetit, reliquis hominibus etiam cupiet et eo magis quo majorem Dei habuerit cognitionem.) After proving his claim, Spinoza observes that the law against killing animals is based more on vain superstition and womanish pity than on sound reason (legem illam de non mactandis brutis magis vana superstitione et muliebri misericordia quam sana ratione fundatam esse). He continues:[22]

| Docet quidem ratio nostrum utile quærendi necessitudinem cum hominibus jungere sed non cum brutis aut rebus quarum natura a natura humana est diversa sed idem jus quod illa in nos habent, nos in ea habere. Imo quia uniuscujusque jus virtute seu potentia uniuscujusque definitur, longe majus homines in bruta quam hæc in homines jus habent. Nec tamen nego bruta sentire sed nego quod propterea non liceat nostræ utilitati consulere et iisdem ad libitum uti eademque tractare prout nobis magis convenit quandoquidem nobiscum natura non conveniunt et eorum affectus ab affectibus humanis sunt natura diversi (vide scholium propositionis 57 partis III). | The rational principle of seeking our own advantage teaches us the necessity of joining with men, but not with beasts, or with things whose nature is different from human nature; we have the same rights against them as they have against us. Indeed, because the right of each one is defined by his virtue, or power, men have a far greater right against beasts than beasts have against men. Not that I deny that beasts feel. But I do deny that we are therefore not permitted to consider our own advantage, use them at our pleasure, and treat them as is most convenient for us. For they do not agree in nature with us, and their affects are different in nature from human affects (see Scholium to Proposition LVII of Part III). |

As flies to wanton boys, are we to th’ gods;Notwithstanding its graphic horrors, the liminary conditions of Dante’s Inferno leave no room for a more adequate way of fitting the punishment to the crime.[24]

They kill us for their sport.

And yet, the logic of this confinement is interdependent with its finality. For the availability of sorrow goes hand in hand with the capacity for contrition and the prospect of redemption. The great sinner’s capacity to experience punishment must be curtailed by a divine decree, lest his response enable him to regain his original place in Heaven, supplanting the infernal scenario of final justice with the endless cycle of revolt and defeat, remorse and redemption. For the prototypical instance of Lucifer’s rebellion against divine authority belies the magnificent promise recounted in the final canto of Dante’s Paradiso:[25]

| A quella luce cotal si diventa, che volgersi da lei per altro aspetto è impossibil che mai si consenta; |

Whoever sees that Light is soon made such that it would be impossible for him to set that Light aside for other sight; |

| però che ‘l ben, ch’è del volere obietto, tutto s'accoglie in lei, e fuor di quella è defettivo ciò ch’è lì perfetto. |

because the good, the object of the will, is fully gathered in that Light; outside that Light, what there is perfect is defective. |

William Blake, River of Light

Is this the Region, this the Soil, the Clime,If the mind is its own place, it can reasonably exempt itself from the measures of eternal damnation, even as it continues to draw upon an infinity of joy found in a single second. We now turn to the details of this defiant equilibrium.[27]

Said then the lost Arch-Angel, this the seat

That we must change for Heav’n, this mournful gloom

For that celestial light? Be it so, since he

Who now is Sovran can dispose and bid

What shall be right: fardest from him is best

Whom reason hath equall’d, force hath made supreme

Above his equals. Farewell, happy Fields,

Where Joy for ever dwells: Hail, horrors! hail,

Infernal world, and thou, profoundest Hell,

Receive thy new Possessor: One who brings

A mind not to be chang’d by Place or Time.

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a Heav’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n.

What matter where, if I be still the same,

And what I should be, all but less than hee

Whom Thunder hath made greater? Here at least

We shall be free; th’ Almighty hath not built

Here for his envy, will not drive us hence:

Here we may reign secure, and, in my choice,

To reign is worth ambition though in Hell:

Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heav’n.

Footnotes:

[0] See Augustine of Hippo, Confessions 11.12.14, translated by E.B. Pusey; Chamfort, Maximes et Pensées, Caractères et Anecdotes, Paris : Garnier-Flammarion 1968, §780 p. 226; Gustave Flaubert, Œuvres, édition établie et annotée par A. Thibaudet et R. Dumesnil, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, Paris : Gallimard, 1951, vol. II, p. 1010; Jules Barbey D’Aurevilly, Les Œuvres et les hommes (1ère série) – III. Les Poètes, Paris, Amyot, 1862, p. 380. All translations, unless noted otherwise, are by MZ.

[1] See Matthew 11.28, translation per The King James Version.

[2] Godlike perfection was mandated by the teachings of Jesus at Matthew 5:48: “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect.” If perfection is possible, the obligation to attain follows from God’s demand of unquestioning obedience. It remains to argue for the possibility. Pelagius appealed to the individual’s need to define himself and his personal values amidst the society ruled by mediocrity and convention. He held out absolute certainty of salvation, available at the cost of absolute obedience to the Divine Law. Man cannot find any excuse for his own sins, either by appealing to the sins of his fathers, or to the corrupting influences of the world. Man alone is responsible for his own shortcomings. Every one of his sins is therefore a deliberate act of contempt against God. See Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000, pp. 340-352; John Passmore, The Perfectibility of Man, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000, pp. 94-115.

[3] See Fusées X.16, OC I, pp. 657-658, reproduced with indications of corrections in manuscript.

[4] See Paradise Lost (1667) 1.587–612, in John Milton, Complete Poems and Major Prose, Merritt Yerkes Hughes (editor), Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2003, pp. 226-227.

[5] See Paradise Lost 1.157-168, in Milton, op. cit., p. 215.

[6] See Isaiah 45.15, 53.3.

[7] See John Plamenatz, Aimez-Vous Rousseau?, The New York Review of Books, Volume 7, Number 11 (29 December 1966).

[8] See Inferno, Canto 3, 18.

[9] Socrates entreats the friends of Gorgias at 523a-527e, to give ear to a right fine story (καλός λόγος), which he expects them to regard as a fable (μῦθος), but intends as an actual account (λόγος … ἀληθής). He speaks of Zeus appointing his sons to be judges of the newly dead; two from Asia, Minos (Μίνως) and Rhadamanthus (Ῥαδάμανθυς), and one from Europe, Aeacus (Αἴακος). Since their death these three sit in judgement in the meadow at the dividing of the road, whence are the two ways leading, one to the Isles of the Blest, and the other to Tartarus. And Rhadamanthus tries those who come from Asia, and Aeacus tries those from Europe, and Minos renders the final decision, if the other two be in any doubt. And so they are free to contemplate each soul (ψυχή) as it might be scourged (διαμαστιγόω) with the work of perjuries and injustice (ἐπιορκιῶν καὶ ἀδικίας) or awry (σκολιά) through falsehood and imposture (ὑπό ψεύδους καὶ ἀλαζονείας) or full fraught with disproportion and ugliness (ἀσυμμετρίας τε καὶ αἰσχρότητος) as the result of an unbridled course of fastidiousness, insolence, and incontinence (καὶ τρυφῆς καὶ ὕβρεως καὶ ἀκρατίας). These souls they consign to punishment in the netherworld. But when the judge discerns another soul that has lived a holy (ὅσιος) life in company with truth (μετ' ἀληθείας), especially one belonging to a philosopher (φιλόσοφος) who has minded his own business and not been a busybody (πολυπραγμονέω) in his lifetime, he is struck with admiration and sends it off to the final reward. As regards the definitive and final nature of hell, see Jonathan Kvanvig, Heaven and Hell, in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

[10] See Matthew 5.22, 29-30.

[11] See Matthew 10.28.

[12] See Matthew 8.12 and 13.42.

[13] See Matthew 25.41, 46.

[14] Sisyphus the craftiest (Σίσυφος) is best known today thanks to the allegory of Albert Camus in Le Mythe de Sisyphe. His lot is recounted by Homer in Odyssey XI, 593-601. Avoided by Dante amidst the giants in the Ninth Circle, resides the giant Tityus (Τιτυός), whose mere attempt to rape Latona, mother of Apollo and Diana, causes his eternal torment by a vulture continuously feeding on his constantly regenerating liver. See Apollodorus, Library and Epitome, 1.4.1 and Homer, Odyssey VII, 324 and XI, 576-581. The poets of Rome painted vivid images of Tituys’ punishment. See Virgil, Aeneid, VI.595-600 and Ovid, Metamorphoses, IV.455-459.

[15] See Summa Theologica, Prima Pars, Quaestio 63, Articulus 2.

[16] See Summa Theologica, Prima Pars, Quaestio 63, Articulus 7, ad primam objectionem.

[17] See Meno 77c-78b.

[18] See Inferno, Canto 3, 1-18, translated by Allen Mandelbaum.

[19] See Convivio 2.13, translated by Richard Lansing, 1998.

[20] See Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 6.2.1139a, cf. 6.2.1139b18-36 and 6.2.1140b31-1141b18; translated by H. Rackham. See the discussion of some issues arising in the transition from specific to general applications of deliberation in David Wiggins, “Deliberation and Practical Reason”, in Essays on Aristotle’s Ethics, Amélie Oksenberg Rorty (editor), Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980, pp. 221-240. Our conclusions are supported by the infernal privation from even the weakest capacity for deliberation, implicit in Dante’s dictum.

[21] See Inferno, Canto 34, 28-69, translated by Allen Mandelbaum.

[22] See Ethica, Pars Quarta: De Servitute Humana Seu De Affectuum Viribus, Propositio XXXVII, Scholium I, translation by Edwin Curley, modified by MZ.

[23] See William Shakespeare, The Tragedy of King Lear, IV.i.37-38, in The Collected Works, edited by Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor, John Jowett, and William Montgomery, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988, p. 964.

[24] For a general overview of penology, see the articles by Hugo Adam Bedau, Punishment and Antony Duff, Legal Punishment, in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. See H.L.A. Hart, Punishment and Responsibility, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968, for a classic and detailed account.

The principle of proportionality that requires punishments to be, in some more or less definite measure, proportionate in their severity to the seriousness of the crime, was derived by Cesare Beccaria, in his treatise Dei Delitti e delle Pene (On Crimes and Punishments), from arguments by Montesquieu. Retributivism and the attendant principle of proportionality are epitomized by F.H. Bradley in an influential summary of Hegel’s gnomic conception of punishment annihilating the crime:

I am not to be punished, on the ordinary view, unless I deserve it. Why then (let us repeat) on this view do I merit punishment? It is because I have been guilty. I have done ‘wrong’. I have taken into my will, made a part of myself, have realized my being in something which is the negation of ‘right’, the assertion of not-right. Wrong can be imputed to me. I am the realization and the standing assertion of wrong. Now the plain man may not know what he means by ‘wrong’, but he is sure that, whatever it is, it ‘ought’ not to exist, that it calls and cries for obliteration; that, if he can remove it, it is his business to do so; that, if he does not remove it, it rests also upon him, and that the destruction of guilt, whatever be the consequences, and even if there be no consequences at all, is still a good in itself; and this, not because a mere negation is a good, but because the denial of wrong is the assertion of right.See F.H. Bradley, Ethical Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1952, Essay I, The Vulgar Notion of Responsibility in Connection with the Theories of Free-Will and Necessity, pp. 1-51, at pp. 27-28; compare G.F.W. Hegel, Philosophy of Right (Die Philosophie des Rechts), First Part: Abstract Right, iii Wrong, §§82-103, passim. A more recent treatment by Murray N. Rothbard is found in The Ethics of Liberty, New York: New York University Press, 2002, Chapter 13, Punishment and Proportionality.

Punishment is the denial of wrong by the assertion of right, and wrong exists in the self, or will, of the criminal; his self is a wrongful self, and is realized in his person and possessions; he has asserted in them his wrongful will, the incarnate denial of right; and in denying that assertion, and annihilating, whether wholly or partially, that incarnation by fine, or imprisonment, or even by death, we annihilate the wrong and manifest the right; and since this as we saw, was an end in itself, so punishment is also an end in itself.

The current American legal standard, established by the U.S. Supreme Court in Ford v. Wainwright, 477 U.S. 399 (1986), holds that an individual is competent to be executed if he understands that he is to be executed and the reasons for his execution. As described by Dante, the sinners consigned to Hell are capable of reciting the reasons for their everlasting punishment, which is the divine counterpart to human execution. But their postulated lack of capacity for moral deliberation deprives them of any chances of understanding the presumptive justice of their predicament.

[25] See Paradiso, Canto 33, 100-105, translated by Allen Mandelbaum.

[26] See Paradise Lost 1.242-263, op. cit., pp. 217-218.

[27] Here ends the umpteenth chapter of the second part of the book previously entitled Representation and Modernity, begun in 1986 and submitted by the author and accepted by Hilary Putnam and William Mills Todd III, in partial satisfaction of 1993 degree requirements at Harvard University. Some of the subsequent chapters have been posted elsewhere in this journal. Comments, questions, suggestions, and requests shall be gratefully considered and promptly answered.

Crossposted to

no subject

Date: 2011-01-23 11:36 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2011-01-26 02:17 am (UTC)no subject

Date: 2011-02-16 01:21 pm (UTC)Incapacità, le soluzioni salutari

Date: 2012-02-28 05:55 am (UTC)Il Viagra è un compresse avvezzo con lo scopo di dissertare la alterazione erettile maschile, promemoria ancora come ED se no impotenza. Si presenta su regola a causa di pillola, copiosamente famosa lato la acuto degli anni 90 quando il profitto fu rilasciato a la prima circostanza al aperto. http://compraviagraitalia.com Utilizzando sostanze chimiche specifiche, il farmaco contribuisce a prolungare le happening sessuali degli uomini ed è il miglior medicinale del emporio per valorizzare la forza sessuale mascolino.

buy viagra 348 3320

Date: 2012-10-20 02:31 pm (UTC)